Suicide is an irrevocable act with implications not just for individuals but also their families and communities. It stems from intense feelings of despair and hopelessness, and when it happens, loved ones often ache to know: Why? Why did their son, daughter, sibling, friend, or colleague take their own life? However, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data has found that the reasons for taking this tragic step don't just lie with the individual; they often ripple out to societal reasons.

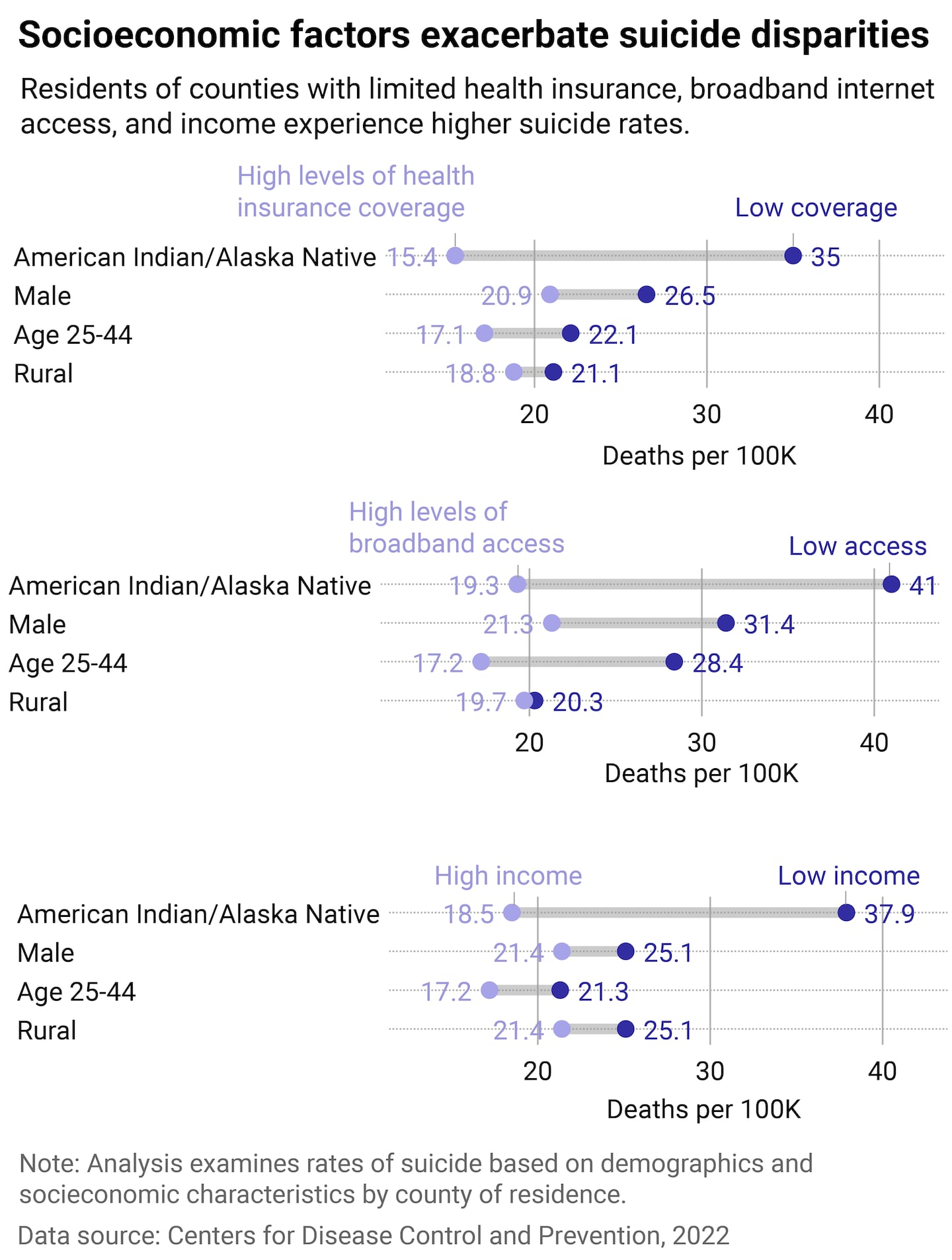

A 2024 CDC report revealed that insurance coverage, lack of access to broadband internet, and household income—systemic factors—all contribute to higher rates of suicide. Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to analyze CDC data describing the socioeconomic factors behind suicide and highlight some of the novel efforts to combat it.

Despite a small slump between 2018 and 2020, suicide rates have risen by 37% since 2000 in the United States. On average, a person dies by suicide every 11 minutes. Suicide is a preventable crisis, but a report from the Commonwealth Fund showed that the U.S. had the highest suicide rate when compared to 10 other high-income nations, despite spending more on health care.

In the past two decades, suicide rates have continued to rise in all age groups. The risk for suicide is highest for people aged 25 to 64. When disaggregated by race, American Indian and Alaska Native people—followed by white people—have the highest rate of suicide. Native youth are particularly at risk. Suicide rates for this group are 2.5 times higher than the overall national average. In a systematic review published in Frontiers in Psychiatry, researchers found that young populations aged 15 to 29 living in isolated rural communities, particularly in low-income communities and single-parent households, tend to be at higher risk, calling out that suicide frequency is higher for those "native, racial and ethnic groups."

The rise in suicides in the country has continued despite the launch and increased use of the federal 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline in 2022. Even so, Lifeline continues to address the problem by rolling out greater specialized services for various populations, including LGBTQ+ people, Native communities, and older adults. What is clear from the CDC's study: local socioeconomic factors shape the effectiveness of suicide prevention efforts.

Suicides are 26% lower in counties with the highest health insurance coverage, 44% lower in areas with better broadband internet access, and 13% lower in those with higher household incomes. "Improving the conditions where people are born, grow, live, work, and age is an often overlooked aspect of suicide prevention," said Alison Cammack, health scientist and lead author of the CDC report. Cammack also pointed out that localized programs "can help people avoid reaching a crisis point."

Northwell Health

An insidious, systemic cause of death, especially for American Indians and Alaska Natives

According to Alutiiq/Sugpiaq Nation member Kaili Berg, writing for Native News, keeping in mind historical trauma and culturally competent care are both important considerations that health institutions should keep in mind to create suicide prevention programs for Native youth.

Writing for Relias, Amanda Gibson—a critical care nurse for 15 years and a member of the Cherokee Nation—expressed that enhancing cultural competence and responsiveness is only one of many factors in improving mental health services in Native communities. Gibson further noted that the most important strategy addressing the root causes of these issues is by targeting the social, economic, political, and cultural determinants of health, which include reducing poverty, creating jobs, improving access to education, cultural preservation, and healing historical traumas.

As systemic solutions continue to be identified and built out, there are a few approaches that have shown success. A study published in the journal Telemedicine and e-Health in March 2022 described how American Indian communities in Montana used telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. It found that 3 in 4 respondents agreed telehealth was effective in suicide prevention. Nearly all (98%) said telehealth was needed. The positive reception to this effort underscores the need to explore increasing investments in telehealth technologies for American Indian communities. American Indian and Alaska Native tribal areas tend to have the lowest broadband internet access in the country, according to the Census.

Narrowing the digital accessibility gap

There are ongoing government efforts to mitigate this lack of access. All 50 states, including the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, are working on digital equity plans to narrow the gap between those who have access and those who have not. Three grant programs that total $2.75 billion under the Digital Equity Act have been set aside for these efforts.

Maine is the first state to have an approved plan by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration. In February 2024, the state unveiled its Digital Equity Plan, created in consultation with 13 regional and tribal broadband partners and as many as 180 coalition institutions. Its key projects include increasing enrollment in its Affordable Connectivity Program by 84,000 households, distributing 50,000 free or low-cost computer devices, and providing digital skills training to 50,000 people—all by 2029.

Increased digital access may also alleviate loneliness and social isolation, which have been linked to mental health issues. But the Navajo Nation knows suicide prevention takes more than an internet connection—having a village is just as vital.

For this reason, in 2024, Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren declared September Navajo Nation Recovery and Suicide Prevention Month. The nation's Division of Behavioral and Mental Health Services includes comprehensive holistic services and out-of-the-box approaches such as individual, group, and family therapy; adventure-based counseling; cultural and spiritual services; and both residential and outpatient treatment programs. The 2020 Navajo Nation Mortality Report showed that intentional self-harm for males dropped from the fifth to the sixth leading cause of death. Efforts like these could help even lower the number of lives lost.

Policy changes in health care, gun safety, and more can make a difference

Health insurance coverage and financial stressors can also be determinants in suicide prevention. Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, many states had the opportunity to expand their Medicaid eligibility for low-income adults, which 39 states adopted by 2021. Apart from improving death from diseases associated with cardiovascular diseases and cancers, increased access to health care through the program has also been found to benefit mental health, leading to fewer suicide incidents.

A joint 2022 study by the Washington University School of Medicine and the Duke University School of Medicine found a lower suicide mortality rate in states that have adopted Medicaid expansion. This increased access to health care not only allowed for better access to preventative mental health services but also helped to reduce individual and family financial strain. Non-Hispanic white individuals aged 30 to 44 and individuals without a college degree showed significantly lower rates of suicide with Medicaid expansion than any other group.

The same researchers also identified stricter gun laws and opioid prescribing laws as possible determinants in lowering suicide rates. Firearms were used in more than half of suicides in 2022. The top three states for gun ownership also fall within the top five states with the highest suicide rates in 2021, according to the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

There is no single solution to suicide prevention, but research shows that when community leaders, policymakers, health care providers, and families listen to the needs of those most at risk, lives can be saved. As suicide rates continue to climb, continuing to invest in better support networks and policies is critical to find the social, technological, and systemic interventions needed to keep communities healthier—and safer.

If you or someone you know are experiencing a mental health crisis or thoughts of suicide, call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 9-8-8 for professional help.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Paris Close.

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.